If you’re new to making music or using beats in your content, you’ve probably seen terms like “copyright-free beats” or “royalty-free music” floating around. But what do they actually mean? Navigating music copyright can be confusing for beginners, yet it’s super important to understand so you don’t accidentally get into legal trouble by using a beat you’re not allowed to. In this article, we’ll break down the concepts of copyright, royalty-free, public domain, and Creative Commons in simple terms. By the end, you’ll know what makes a beat truly “copyright-free” (and why that term isn’t as straightforward as it sounds). We’ll also use examples – including how AI-generated music (like from SOUNDRAW) is handled – to illustrate these ideas. Let’s demystify music rights!

Understanding Copyright in Music

Copyright is a legal term that grants the creator of an original work (like a music composition or recording) exclusive rights to its use and distribution. In plain language: if you make a beat from scratch, you automatically own the copyright to that beat (you don’t have to file anything; it’s your property by default). This means others can’t legally use your beat in their projects (videos, songs, etc.) without your permission – unless an exception applies (like fair use, which is limited and case-specific).

For music, there are actually two copyrights to consider:

- The composition (melody, chords, lyrics – the songwriting aspect).

- The sound recording (the actual audio file/recording of the performance).

For a beat you produce, you likely own both (unless you’re using someone else’s melody or samples without permission).

When we say a beat is “copyrighted,” it means someone owns it and has rights over it. When people search for “copyright-free music,” they generally mean music they can use without infringing on someone’s rights or getting a copyright claim on platforms like YouTube. However, the term “copyright-free” is a bit misleading, which brings us to the next section.

“Copyright-Free” vs “Royalty-Free” – What’s the Difference?

Often, “copyright-free” music refers to music in the public domain (more on that later) or music the creator has explicitly waived rights to. True copyright-free music means nobody owns exclusive rights to it – you can use it however you want, no strings attached. This is relatively rare for modern music because most creators don’t just give up their rights for nothing.

On the other hand, “royalty-free” music is a much more common term you’ll encounter. Royalty-free does not mean “no one owns the copyright.” In fact, royalty-free music is very much copyrighted – it’s just offered to users under a special license where you pay once (or not at all) and then you can use the music without paying additional royalties each time. Royalties are recurring payments to the copyright holder (for example, paying a fee every time a song is played on the radio). With royalty-free, you either pay a one-time fee or meet certain conditions, and then you don’t have to pay for each use.

Think of it this way:

- Royalty-Free: “You can use my copyrighted music, usually after buying a license or under certain conditions, and you won’t owe me any ongoing payments.” The creator/composer retains the copyright, but gives you broad permission.

- Copyright-Free: “This music has no owner or all rights have been waived; you can use it however you want without permission.” Essentially, it’s as if the music is owned by the public.

Most of the time when you see “free beats” or “free music for videos,” they are actually royalty-free (under license) rather than truly copyright-free. For example, a beat maker on YouTube might say “free for non-profit use” – that’s them licensing it to you for certain uses (non-commercial) without charge, but they still own the copyright and could impose conditions (like requiring credit or prohibiting commercial release unless you pay).

To ensure we’re clear:

- If a beat is copyright-free, you don’t need any permission to use it; it’s like using a folk song from the 1800s that’s long in the public domain – no one will sue you.

- If a beat is royalty-free, you typically need to adhere to a license. Maybe you bought it from a site like Epidemic Sound or got it from a creator who said “just credit me, and it’s free to use.” The creator still could enforce their copyright if you violate terms (like if you used it in a way not allowed).

Now, let’s break down some categories of music that people often use when they want “no copyright issues.”

Public Domain: Truly No Copyright Attached

Public domain music is music that is not protected by copyright, usually because the copyright has expired or the creator intentionally put it into the public domain. When music enters the public domain, anyone can use, modify, and distribute it for any purpose without needing permission or paying fees. It’s truly “no strings attached.”

How does music become public domain?

- Age/Expiration: Copyright on a composition lasts the life of the author plus a number of years after their death (the exact number varies by country – often 70 years). For sound recordings, it can be 70 to 95 years from publication, again depending on laws. So, very old music (classical pieces by Beethoven, folk songs from the 19th century, etc.) are in the public domain because their composers died long ago and the copyrights expired. You can perform or use those compositions freely. But caution: A specific recording of a Beethoven symphony by an orchestra could still be under copyright (the performance is newer), even though the notes (composition) are public domain. So you might need to use recordings that are also public domain or make your own.

- Waiver (CC0): Sometimes, creators will release their work under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, which effectively places it in the public domain intentionally. This is like saying “I give up my rights, anyone can use this.” Some free music libraries or individual artists do this to allow maximum freedom. For example, you might find CC0 music on sites like Free Music Archive or certain YouTube Audio Library tracks designated as such. If a beat is CC0, you can use it in your commercial project, remix it, etc., with no need to credit (though it’s nice to).

Example: The song “Happy Birthday” was under copyright for a long time (which is why you rarely heard it sung in movies), but it entered public domain a few years back after a legal battle, so now it’s free to use by everyone. Similarly, a traditional song like “Greensleeves” is public domain – no one will come after you for using that melody.

If you truly want a “copyright-free beat,” you’d have to find one in the public domain or CC0. There are some available, but most contemporary-sounding beats won’t be public domain (since they haven’t been around long enough). That’s why many content creators instead use royalty-free music.

Royalty-Free Beats and Music

We touched on royalty-free already – let’s expand with an example to cement the idea. Consider a platform like Epidemic Sound or Artlist. These are royalty-free music libraries. How they work is: you pay a subscription, and then you can use any music from their catalog in your videos, without needing to pay the artist each time or worry about YouTube strikes. You’ve essentially bought a license that covers you. The music is still owned by someone (often the platform or the original artists who have an agreement), but they won’t claim your video because you’re covered under that license.

In another scenario, a producer might sell a beat as a royalty-free license. For example, you pay $30 for a beat on a site like Beatstars and the producer grants you the right to use it in your own song and distribute X number of copies without additional payments. The producer keeps the copyright, but you have clear permission to use it within the agreed terms.

To be safe when using “royalty-free” music:

- Read the terms. Some royalty-free music is free to use even commercially with just attribution (like many tracks on YouTube Audio Library or Incompetech by Kevin MacLeod). Others require that you don’t redistribute the music by itself or claim ownership.

- Royalty-free doesn’t automatically mean you can use it for anything. For instance, some royalty-free tracks are free for YouTube but not for film, or free for personal use but require a fee for commercials. Always check the license specifics (e.g., is it Creative Commons Attribution? Is it free for non-commercial? etc.).

A quick note on the term “No Copyright Music” (often seen on YouTube with titles like “No Copyright Chill Beat…”): Usually, this is a shorthand for “we (the creators) won’t issue copyright strikes if you use this,” which again usually implies a royalty-free license. It doesn’t mean the music isn’t actually copyrighted – often it is, but the creator is giving general permission. Always double-check the description; reputable channels will state the terms (like “free to use in monetized videos with credit to the channel”).

Key takeaway: Royalty-free music simplifies life for content creators. It’s typically what you want if you’re looking to avoid copyright issues. Just make sure you obtain it from legitimate sources and follow any stated rules (like crediting the artist or platform if required).

Creative Commons Licenses: Free Use with Conditions

Creative Commons (CC) is a framework of licenses that creators can use to give others permission to share and use their work under certain conditions. It’s like a menu of “some rights reserved” options, as opposed to the default “all rights reserved” of full copyright. Music released under Creative Commons is not public domain; the creator still holds copyright, but they allow everyone to use it in specific ways.

The common Creative Commons licenses you’ll see for music are:

- CC BY (Attribution): You can use the music for any purpose (even commercial), remix it, etc., as long as you credit the original creator. This is pretty flexible.

- CC BY-SA (ShareAlike): Similar to CC BY, but if you remix or use the music in something, you must release your new creation under the same license. (This is somewhat common in open-source music communities).

- CC BY-NC (NonCommercial): You can use, tweak, share the music as long as it’s not for commercial purposes. This is important – “noncommercial” means you can’t make money directly from it. Using an NC-licensed beat in a YouTube video that you monetize is likely a violation (because monetization = commercial use). So be cautious with NC if you intend any profit.

- CC BY-ND (NoDerivatives): You can use it, but you can’t modify it or create derivatives – basically you have to use it as is. (For a beat, that would mean you can’t, say, chop it up or add vocals? ND is less common for music, because a lot of usage is inherently derivative. But it exists.)

- There are combinations like CC BY-NC-SA, CC BY-NC-ND, etc., which mix the above conditions (non-commercial + share alike, etc.).

Creative Commons is popular on sites like ccMixter, Free Music Archive, and among independent artists who want their music to spread. For example, an artist might put out a beat under CC BY, meaning “sure, use my beat, even commercially, just give me a shoutout in the credits.” This is a great way for beginners to find music they can use legally without paying, as long as they honor the license.

Example: You find a cool chillhop beat by an artist on SoundCloud labeled “CC BY 4.0.” You use it as background music in your vlog and in the YouTube description you write, “Music by [Artist Name] – used under Creative Commons Attribution License.” That should satisfy the attribution requirement (and keep evidence of permission). If it were CC BY-NC, you’d ensure you’re not monetizing that video.

Always double-check the exact CC license version (e.g., 3.0, 4.0) and conditions. The good thing about CC licenses is they are standardized and globally recognized – you can read the human-readable summary on creativecommons.org for any license type.

What Does “Copyright-Free Beat” Really Mean Then?

Given the above, when someone says “copyright-free beat,” they usually mean one of two things:

- The beat is in the public domain – either really old (not likely if it’s a modern style beat) or released as CC0.

- They mean “royalty-free” or “no copyright claims” – the terminology is used loosely. Often producers or platforms will say “copyright-free” as shorthand for “we won’t Content ID flag you” or “this is free to use.” Technically the beat still has copyright, but the user has permission.

For instance, the YouTube Audio Library offers music that’s free to use. Some tracks require attribution, some don’t. Those can be considered “copyright-free” from the user’s perspective because YouTube has ensured those tracks won’t trigger copyright claims on your videos (YouTube has either secured rights or the artists agreed). But behind the scenes, either YouTube or the artist holds the copyright – they’ve just given you a broad license (often akin to royalty-free).

Important: If you see “free beat – no copyright” on the internet, ensure you have proof of the terms. If it’s from a random website, there should be a clear statement like “This beat is free to use in any project, no attribution needed” or something. Save that or get a license document if possible. There have been cases of people using “free” beats that later got claimed because maybe the producer changed their mind or uploaded to Content ID. Ideally, get beats from reputable sources with explicit licensing info to be safe.

AI-Generated Music and Copyright

Now, an interesting modern question: If an AI generates a beat, who owns it? Is it copyright-free by default? The answer is evolving and can depend on the platform and jurisdiction.

Under current U.S. copyright law (and similarly in some other countries), works created entirely by a machine with no human input might not qualify for copyright because there’s no human author to attribute (copyright traditionally requires a human creative element). This suggests that a purely AI-created piece of music could be considered not protected – potentially public domain. However, this is a gray area and not fully tested in courts for music yet. Plus, AI platforms often have terms of service that address ownership.

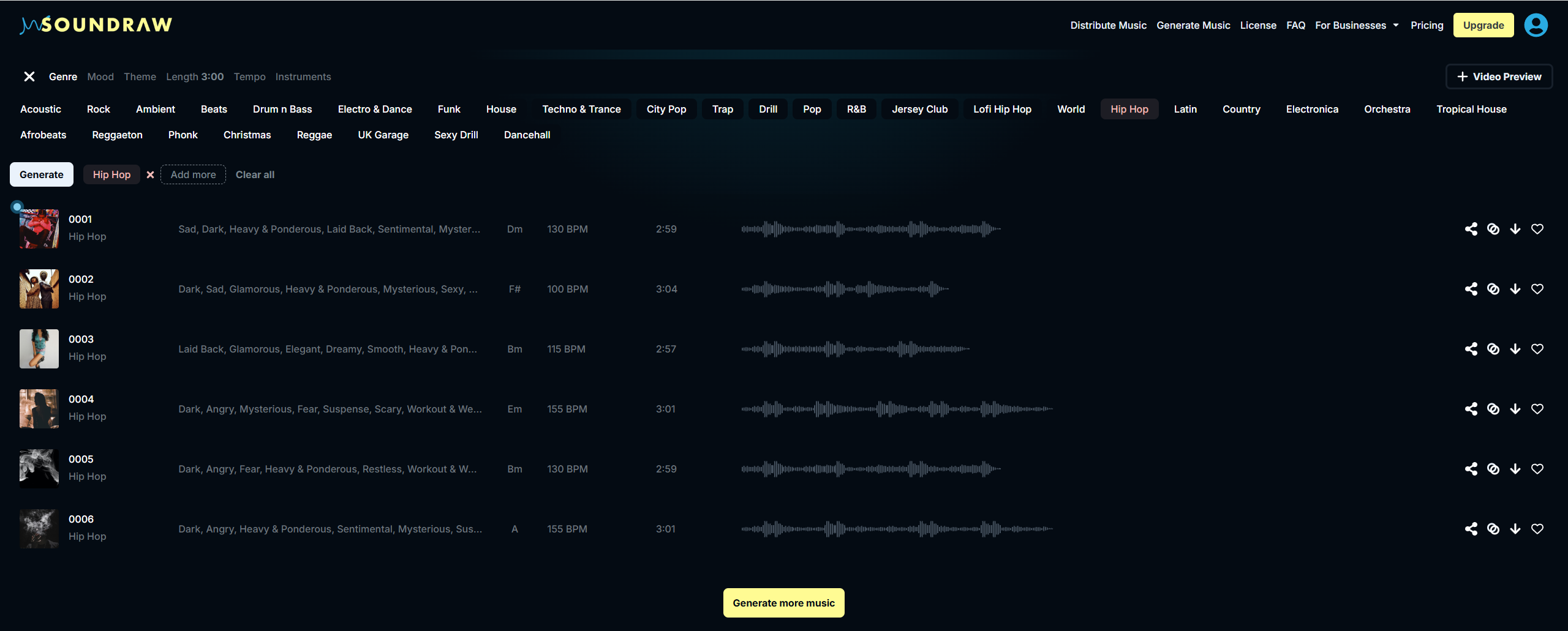

Many AI music generators, like SOUNDRAW, AIVA, Boomy, etc., have their own policies:

- SOUNDRAW’s policy: SOUNDRAW retains full copyright ownership of all music generated on its platform. They then license it to the users. When you subscribe and download a track, you get a license to use it in your content forever. But you are explicitly not allowed to register that music in YouTube Content ID or claim it as your own copyrighted material. This is to keep it “royalty-free” for all users – if you tried to claim it, you’d be asserting exclusive rights which you don’t have. SOUNDRAW guarantees no one else will successfully claim it either, as they register it on their end to prevent random claims. So SOUNDRAW-generated beats are royalty-free for subscribers but not copyright-free in the sense of public domain – the company holds the copyright and ensures the music is safe to use.

- Boomy’s policy: Boomy actually lets users own the copyright of songs they create, to the extent possible. When you create a Boomy track, you are listed as the artist if you release it. However, Boomy’s terms likely have clauses that the music must remain on their platform’s good graces. (Boomy had an incident where a lot of songs were removed for streaming abuse, showing they do manage rights actively). It’s a bit complex, but effectively, Boomy tracks are original enough that you can register them as yours if you wanted to distribute beyond Boomy’s own process.

- AIVA’s policy: AIVA historically allowed users to claim authorship of tracks they create (AIVA even got itself recognized as a composer in Luxembourg for a while). But they also provide a license. AIVA’s website says you can use its generated compositions with a free plan for non-commercial and with paid plans for commercial, etc. So again, you’re operating under a license.

The big picture: AI-generated music is often sold as “royalty-free” – you won’t pay royalties and you won’t get strikes, but it doesn’t necessarily mean “no one owns it.” Either the user might own it (if the AI service gives you that right) or the company might own it and just let you use it widely.

From a legal standpoint, the copyrightability of AI music is still being figured out. As of early 2025, there have been cases for AI-generated art where the US Copyright Office said “no” to pure AI images being copyrighted by the creator, because the creator didn’t do the traditional authorship. But some AI companies assert control via contract.

Implications for you as a beginner: If you use an AI tool to make a beat, read their FAQ or terms about usage:

- SOUNDRAW: you’re safe to use it in content, but you can’t, say, re-sell the beat or upload it to a music distribution as is without modifications (unless you have their Artist plan and add your own elements as required).

- If you heavily modify an AI beat (add vocals, additional instrumentation), some argue that end result has human creativity and could be copyrighted by you in that combined form. SOUNDRAW explicitly says if you add your vocals, you can release that commercially (with the right plan) as long as the final song is clearly different from the raw AI track.

- The nice thing about AI platforms: they often guarantee royalty-free usage and no copyright strikes. SOUNDRAW’s blog even likens AI-generated music to “royalty-free elements” that won’t lead to lawsuits like sampling someone else’s work would. So using AI beats can be a safe way to have background music or even create songs without worrying about infringing on another artist’s copyright – as long as you abide by the tool’s terms.

In summary, AI music isn’t automatically public domain, but it is typically provided under a license that makes it functionally copyright-issue-free for you as a user. It’s one reason a lot of creators are excited – you can generate unique music and not fret over YouTube claims, since the AI company ensures those tracks aren’t in the Content ID system wrongly.

Quick Recap with Examples:

- Copyrighted beat (all rights reserved): You found a random Drake-type beat on someone’s SoundCloud. If you use it without permission, you’re infringing. If you want to use it, you need the producer’s explicit license (e.g., purchase a lease).

- Royalty-Free beat: You subscribe to a site like Artlist and download a beat. You can use it in your YouTube video; the video gets claimed by Artlist’s system but they auto-clear it because you have a license. You paid once (your subscription) and no more fees even if the video gets millions of views.

- Public Domain music: You use Beethoven’s “Für Elise” melody in your beat. The melody composition is public domain – you can do that. But if you sampled a specific recording of “Für Elise,” you must ensure that recording is also PD or you recorded it yourself.

- Creative Commons example: You get a beat from an artist who released it under CC BY-NC. You use it in a fun Instagram video (non-commercial) and credit them – totally fine. But then you decide to put that video on YouTube and monetize – now it’s commercial, and that violates the NC license. The artist could file a claim.

- SOUNDRAW AI beat: You generate a lo-fi beat on SOUNDRAW and use it as background music in your Twitch stream. It’s royalty-free for you; SOUNDRAW’s copyright bots won’t strike you (and if some automated system does, SOUNDRAW will support resolving it). You’re safe to use it. However, you do not try to upload that track to Spotify as your own single without changes – that would conflict with SOUNDRAW’s terms (unless you’ve modified it sufficiently and have their appropriate plan).

How to Ensure a Beat is Safe to Use (Checklist)

- If it’s your own original beat: You’re the copyright owner. No issues there (just be sure you didn’t unknowingly use un-cleared samples).

- If using someone else’s beat: Look for a license or terms of use. Is it labeled royalty-free? Public domain? Creative Commons? Free for nonprofit? Only use it if you can find a clear statement of permission that covers your intended use. When in doubt, reach out to the creator for clarification.

- Get documentation: Many royalty-free purchases come with a license PDF. Keep those. For Creative Commons, take a screenshot of the page showing the CC license in case you need to prove it later.

- Credit when required: If the license (like CC BY) says to give credit, do it in the description or credits of your project. It’s a simple step that fulfills the license and also is courteous to the creator.

- Avoid “Free beats” that seem too good without any info: If someone just says “yeah bro use my beats free,” that’s nice, but get it in writing if possible (even an email). There have been scenarios where a beat was free, then later the producer signed it to a library or label and suddenly it started getting claims. If you had an agreement, you’d be in a better position.

- Public domain verification: If you think something is PD (like an old song), double-check the country’s rules. In the U.S., virtually anything published before 1928 is public domain as of 2025. Each new year, works from 95 years ago enter PD. But if it’s on the cusp, confirm.

- AI music: Just use reputable AI services that explicitly grant you rights. Read their FAQ about “Can I use this music on YouTube/for commercial projects?” Most will proudly say yes and describe how (since it’s a selling point). Keep an eye out for any restrictions (like SOUNDRAW’s Content ID rule).

Conclusion

A beat is “copyright-free” in the strictest sense only if nobody has an exclusive right over it – typically meaning it’s public domain. In practice, most beats you encounter will have some owner, but many are made available through licenses that give you freedom to use them (royalty-free licenses, Creative Commons, etc.). As a beginner, remember:

- Royalty-free music: You can use it without recurring fees, but there is usually an owner behind it; follow the license terms.

- Public domain music: Truly free – but ensure it’s actually public domain and not just labeled “copyright-free” loosely.

- Creative Commons music: Free with conditions like giving credit or non-commercial use only

- AI-generated beats: Typically safe for use (no royalties, no claims) due to how companies handle licensing, but they are usually not for resale as your own unless significantly modified.

When in doubt, err on the side of caution: seek permission or choose alternatives that you know are safe. There are huge libraries of legal, free music out there now – from YouTube’s own audio library to community-driven sites – so there’s little reason to risk using an unauthorized beat. Understanding these concepts will help you avoid headaches and ensure the music in your projects is both fire and legally cleared. Happy (and lawful) creating!